Life at 32F: Why Structure Eats Culture for Lunch

About 18 years ago I started a biotech company to develop new drugs for treating cancer. Not long after, my father was diagnosed with a rare type of leukemia. I thought I could do something for him, since I had access to all the latest tools and technologies and drug candidates and experts. Nothing helped. A few months later he died.

Over the years, as my company grew, everywhere I looked, inside big companies or small companies, there were promising ideas trapped in the basement of those organizations. Ideas that might helped my father. Or people with other types of cancer or other severe diseases.

Those ideas stay trapped not because any of the people are bad people. Everyone I’ve ever worked with has lost loved ones to cancer or other severe diseases. Everyone wants to go home to their spouse or family and say I’m making a difference. The problem isn’t with any of the people. The problem has to do with what happens when people come together into a group.

Which boils down to one question, one mystery: Why do good teams, with excellent people and the best intentions, kill great ideas?

The answer isn’t culture. Despite the mountains of mind-numbing print written on the subject, there’s something at the core of how large groups behave that we just don’t understand. Every year, glossy magazines celebrate the winning cultures of innovative teams. Covers show smiling employees raising gleaming new products like runners raising the Olympic torch. Leaders reveal their secrets. And then, so often, those companies crash and burn. The people are the same; the culture is the same; yet seemingly overnight, they turn. Why?

There’s a common saying in business that culture eats strategy for breakfast. Let’s talk about something different: why structure eats culture for lunch. Understanding the balance of incentives inside groups gives us a new way to think about the behavior of teams, companies, and even nations — along with a new set of tools to liberate those promising ideas trapped in basements everywhere.

Academic studies conducted by psychologists are occasionally cited to support the idea that incentives don’t matter. In the real world, however, the non-academic but very successful pair of investors Charlie Munger and Warren Buffet once said: “95 percent of behavior is driven by incentives.” Later they amended that to, “The 95 percent was wrong. It’s more like 99 percent.”

So here’s how understanding incentives can help us understand why good teams will kill great ideas.

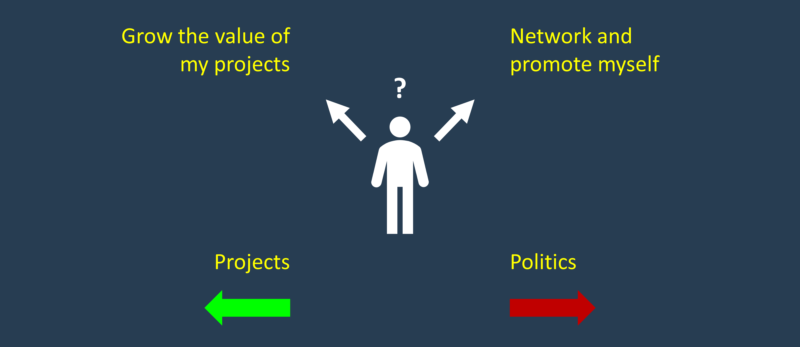

Three people pursuing a big idea may each have a one-third stake in the outcome of the idea (let’s assume all stakes are split equally). The titles they give themselves don’t matter compared to their big stake in the outcome. One person may be “team captain” and the other two may be team members, but whatever perks of rank go along with being captain still won’t matter much compared to those high stakes. All three will roll up their sleeves and do whatever it takes to rescue that idea from the inevitable stumbles of an early stage project.

With 100 people, however, each person will have a 1% stake in outcome. Since 99 people can’t report into 1 person efficiently, the group will need some layers. If each manager has 5 direct reports, for example, there will be a total of 4 layers (1 CEO, 5 SVPs, 25 VPs; the rest are “associates”).

Now which is bigger: perks of rank or stake in outcome? Individual stakes have shrunk to 1%. But the perks of rank might be quite large. A bigger base salary and bonus. A parking space.

As soon as perks of rank outweigh stakes in outcome, individual incentives begin favoring a focus on politics rather than projects. Sometimes those two overlap, but often they don’t, especially in the case of fragile, early-stage ideas. The ones that are easy to write off as crazy.

I call those ideas loonshots because the big ideas, the ones that change the course of science or business or history, rarely arrive with blaring trumpets dazzling everyone with their brilliance. They’re usually dismissed for years or decades, their champions written off as crazy. There wasn’t a good word for that in the English language, so I made one up.

Loonshots arrive covered in warts—the flaws and seemingly obvious reasons they could never work. It’s easy for someone who wants to get ahead to highlight those warts. To make smart comments in group meetings, comments about where the industry is headed and why hasn’t this experiment been done or here’s an obvious weakness, all of which may sound thoughtful, even wise, to others. That person’s boss might be sitting around the table and nod along approvingly. This person knows what they’re talking about, she will think.

If those clever politicians can do that well, consistently, at the right time and place, saying what they think their bosses want to hear, then they might earn themselves a promotion. In which case their base salary might go up by 30%. Which is far larger than their 1% stake in outcome.

It might seem like the “culture” has changed: from a four-person team where everyone chips in to a 100-person group riddled with politics. But underlying that change in culture is a shift in incentives. In other words, structure drives culture.

Readers of Daniel Kahneman’s or Richard Thaler’s work know that behavioral economics helps us understand the reasons why individuals make seemingly irrational decisions. The ideas here help us understand the reasons why groups make seemingly irrational decisions. For example, why good teams kill great ideas. In other words, why teams and companies, like individuals, are predictably irrational.

Here’s why all this matters: changing culture is hard. Changing structure is much easier.

No amount of yelling at the molecules in a block of ice to loosen up a little will get that block of ice to melt. But a small change in temperature can get the job done. A small change in temperature can melt steel.

Let’s see how this works.

Control Parameters

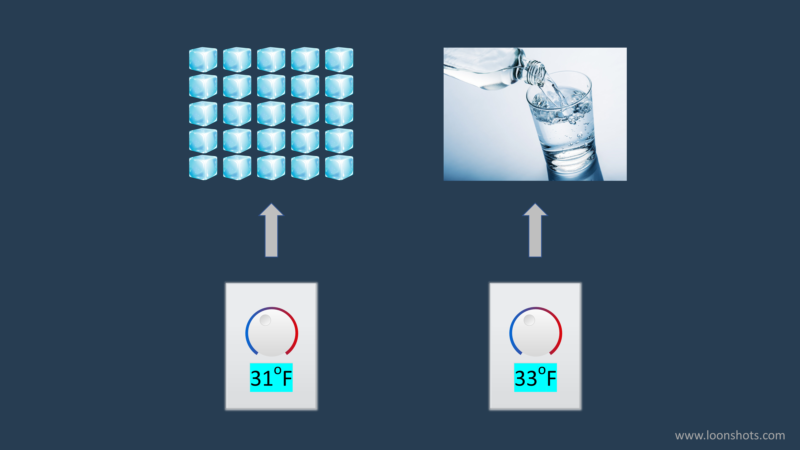

A sudden shift in the collective behavior of a system is triggered by changes in “control parameters.” Temperature is one kind of control parameter: a small change in temperature can transform a flowing liquid into a rigid solid.

The bad news is that these sudden shifts in behavior are inevitable. Just as all liquids will freeze when temperature increases, all groups will shift from innovative to political as size increases.

The good news, however, is that understanding the control parameters allows us to manage the transition. On snowy days, we toss salt on our sidewalks to lower the temperature at which that water freezes. We want the snow to melt rather than harden into ice. We’d rather wet our shoe in a puddle than slip and spend a week in the hospital.

We use the same principle to engineer better materials. Raw iron is a weak metal. Adding a small amount of carbon to iron creates a much stronger material: steel. Adding nickel to steel creates the ultra-strong alloys used inside jet engines and nuclear reactors.

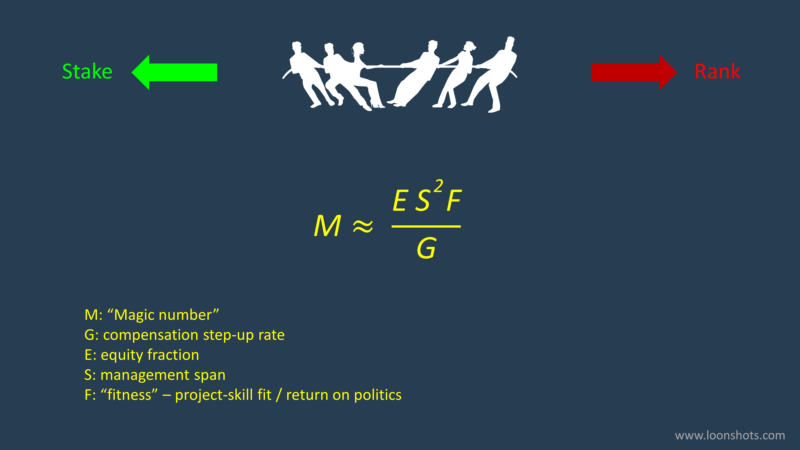

Identifying the equivalent parameters for teams and companies helps us design more innovative organizations. The equation that describes the size M at which a company will snap, when politics will begin to dominate over projects, is described in Loonshots. The four parameters in that equation are the equivalent of sprinkling salt or adding carbon. They are elements of structure that drive culture inside organizations. (For a summary, see “The Innovation Equation” in the Harvard Business Review. For an even shorter summary, see this 17-tweet thread. While you’re at it — see this thread for Cliff notes to the book.)

Life at 32 Fahrenheit

Articles and books on culture scream Innovate or die! The CEO must be the CIO (chief innovation officer)! And so on.

Inventing new products or strategies to stay ahead of competitors is important, of course. But unless a group can consistently deliver those products to customers on time, on budget, on spec, that team or company will eventually get beaten by its competition.

In other words, we need to balance radical innovation with operational excellence.

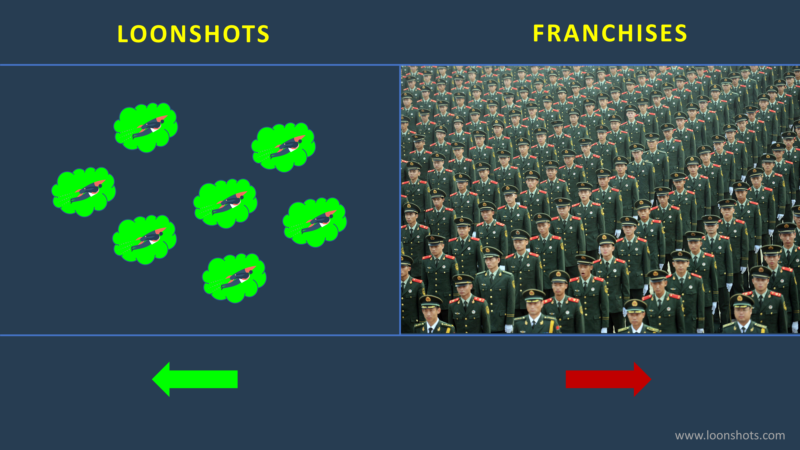

Which is a big problem. We’ve just seen that whenever you organize people into a group you create two competing forces and those forces push you to one of two phases: a loonshot phase in which you’re good at nurturing radical new things, or a franchise phase in which you can excel at delivering on time, on budget, on spec.

The problem is that a system can’t be in two phases at the same time. A glass of water can’t be both liquid and solid.

But companies need to do both, at the same time, as do armies and nations. Armies need to deploy millions of soldiers in battle. But they also need to stay ahead of their enemies in developing the radically new weapons that might turn the course of a war.

So what’s the answer?

Fortunately, there’s one exception to the rule that a system can’t be in two phases at the same time: right on the cusp of a phase transition. Life at 32 Fahrenheit.

Imagine bringing a bathtub full of water to the brink of freezing. A little bit one way or the other and the whole thing freezes or liquefies. But right on the cusp, blocks of ice coexist with pockets of liquid. The coexistence of two phases, on the edge of a phase transition, is called phase separation. The phases break apart—but stay connected.

The connection between the two phases takes the form of a balanced cycling back and forth: Molecules in ice patches melt into adjacent pools of liquid. Molecules of liquid swimming by an ice patch lock onto a surface and freeze. That cycling, in which neither phase overwhelms the other, is called dynamic equilibrium.

Phase separation and dynamic equilibrium, translated back into the world of teams and companies, are the key ingredients to balancing radical innovation and operational excellence.

That means separating your artists working on the new and your soldiers working on the core; tailoring the tools to the phase; leading as a gardener, not a Moses (managing the transfer, not the technology); and—most importantly—learning to love your artists and soldiers equally!

When CEOs and leadership teams ask me to discuss the ideas in Loonshots with them, this is what we talk about. The practical steps leaders can take to bridge the divide between artists and soldiers. In other words, how to achieve life at 32 Fahrenheit.

Structure Vs. Culture

That a word or subject like “culture” has been abused to the point of meaninglessness doesn’t mean it should be dismissed entirely.

Complex systems—the term of art for many interacting agents, whether cars on a highway, buyers and sellers in markets, employees and managers in companies—have earned that term for a reason. Their most interesting questions rarely have simple answers.

In the complex system of our human body, for example, certain genes make diabetes or cancer more likely. But lifestyle choices also matter. Drinking sugary drinks by the gallon can bring on diabetes. Smoking cigarettes by the carton makes lung cancer more likely. Both genes and lifestyle matter.

And so with teams and groups: both structure and culture matter.

The aim of Loonshots is not to replace the idea that certain patterns of behavior are helpful (celebrating victories, for example) and others are less so (screaming at your employees), but to complement it.

In other words, my goal with Loonshots is to give all of us new tools to unleash the important ideas trapped in the basements of companies everywhere.

So the next time someone’s loved one falls ill, we might be faster with an answer.

Read more Letters

Read the Five Laws of Loonshots

“A groundbreaking book that spans industries and time” –Newsweek

“If the Da Vinci Code and Freakonomics had a child together, it would be called Loonshots” –Senator Bob Kerrey