My father and the mystery of how stars shine

The Norse believed the sun god drove a chariot daily from east to west across the sky. The Aztecs believed our sun was fifth in a continuous cycle of suns. The Roman festival Dies Natalis Solis Invicti celebrated the rebirth of the sun god every year (the date, by the way, on the Julian calendar: December 25).

For thousands of years philosophers and rulers praised the divinity of the sun and the stars. In the 1600s, however, those beliefs gave way to a new idea: that underlying everything we see, including the motions of heavenly objects, are universal truths, truths that can be determined through measurement and experiment. In other words, laws of nature.

The rise and spread of that idea over two thousand years—a story of Catholic bishops hiring Jews in Toledo to translate Arab critiques of Greek texts into Latin for Germans to read, of Chinese technologies and Indian mathematics and Islamic astronomy—was closely tied to our urge to understand the sky. Tycho’s comets, Kepler’s ellipses, and Galileo’s telescope proved that the great philosophers and divine rulers had been wrong about heaven and earth.

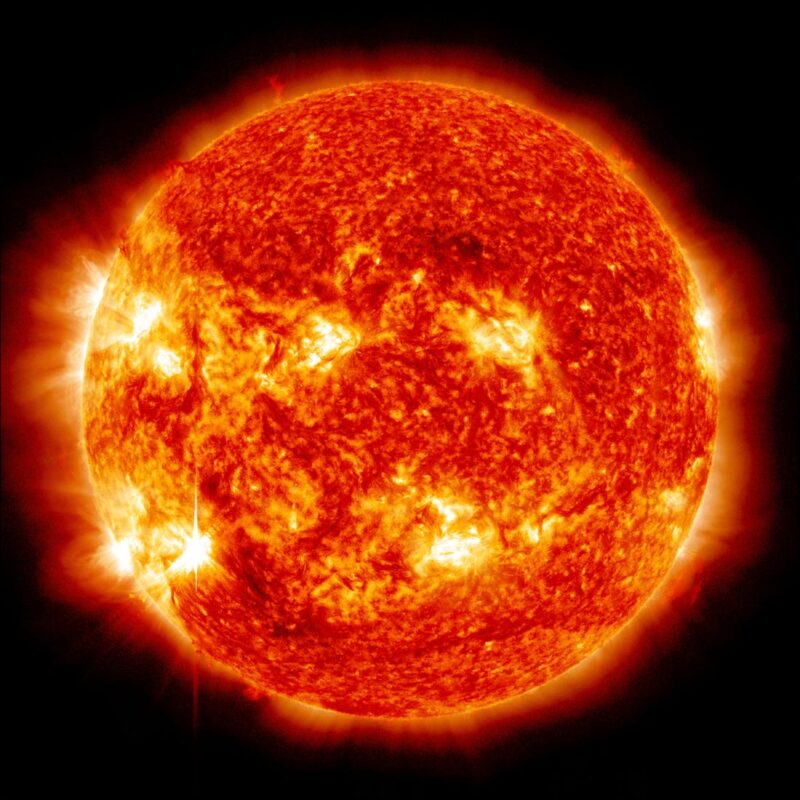

Scholars soon began asking practical questions about the sun: what makes it shine? Is it on fire? If the sun were burning some kind of gas, they realized, it would have exhausted its fuel very quickly, over thousands of years, not the billions of years it has been shining.

For centuries, there was no answer. Then in 1938, Hans Bethe, a 32-year-old assistant professor at Cornell who had fled Hitler’s attacks on German Jewish scientists, came up with a new idea. A nuclear fusion reaction, in which four hydrogen atoms come together to make helium, could release enough energy to power our sun for billions of years.

Today we know that every minute, the sun produces energy equivalent to exploding six trillion one-megaton nuclear bombs. But when Bethe suggested his idea, it was considered crazy.

In 1964, a 29-year-old astrophysicist at Caltech named John Bahcall, my father, proposed a new way to test Bethe’s ideas. My father and Ray Davis, an experimenter based at Brookhaven National Lab in New York, suggested building a new kind of a detector. One that would be placed deep underground and could be used to measure byproducts of the nuclear fusion reactions in the sun: ghostly, massless particles called neutrinos.

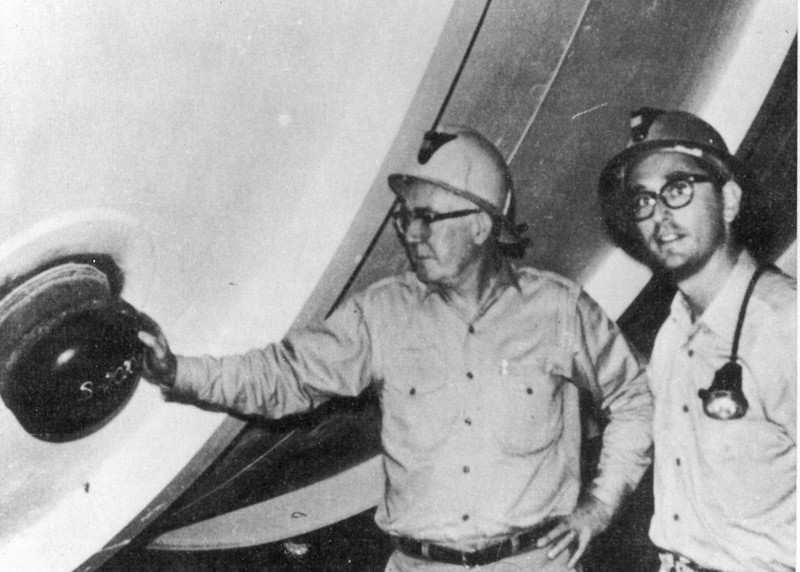

Their idea was also dismissed as nuts. Few believed that we could accurately predict and measure neutrinos arriving on earth from a nuclear explosion 93 million miles away. My father and Davis persisted. Eventually, they scraped together enough funding to build the detector in an abandoned gold mine in South Dakota called Homestake.

My father + Ray Davis, Homestake mine (1964)

Unfortunately, the result of the experiment disagreed with my father’s calculation. They observed 1/3 as many neutrinos as my father had predicted – a discrepancy of a factor of three. Later, that factor of three would become famous and lead to a handful of Nobel Prizes. But at the time my father was very discouraged.

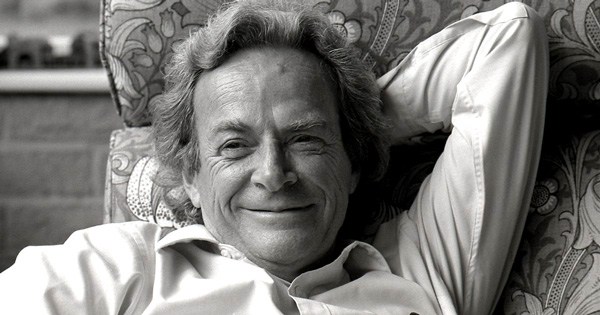

An elder statesman of the field stepped in, the legendary Caltech physicist and Nobel laureate Richard Feynman.

In a Nova documentary about what came to be known as the “solar neutrino mystery,” my father said:

I was very visibly depressed, I guess, and Dick Feynman asked me after the meeting if I would like to go for a walk. He talked to me about inconsequential things, personal things, which was very unusual for him; it never happened before or afterwards in the many years that I knew him.

Toward the end of the walk, which lasted over an hour, he told me, “Look, I saw that you were depressed, and I just wanted to tell you that I don’t think you have any reason to be. Nobody’s found anything wrong with your calculations. I don’t know why Davis’s result doesn’t agree with your calculations, but you shouldn’t be discouraged, because maybe you’ve done something important.”

I think of all of the walks or conversations I have had in my professional life, that was the most important.

Richard Feynman, Caltech

The solar neutrino discrepancy persisted for nearly 40 years. Over that time several more detectors were built to try to solve the mystery of the missing neutrinos.

In 2001, one of the new detectors, the Sudbury Neutrino Observatory in Canada, announced a startling result: my father and Ray Davis had been right all along. It was the laws of physics that were wrong. Neutrinos had a mass. They came in three flavors (the electron, muon, and tau neutrinos) and oscillated between those three, solving the puzzle. My father was quoted in the New York Times saying that when he heard the news, “I felt like dancing I was so happy.”

Shortly afterwards, Hans Bethe, by then 96 but still going strong, sent my father a note congratulating him for his role in helping solve the mystery of how stars shine. My father treasured that note.

The solar neutrino work has been recognized with four Nobel Prizes, the most recent in 2015. (My father passed away in 2005 and the prize is not awarded posthumously.)

The moral of the story: don’t give up.

If something doesn’t work the way you expected, you may have just discovered something important.

That lesson has stayed with me for years. Thanks for that, dad.

Above: my father receiving the National Medal of Science from President Clinton; at home, later.

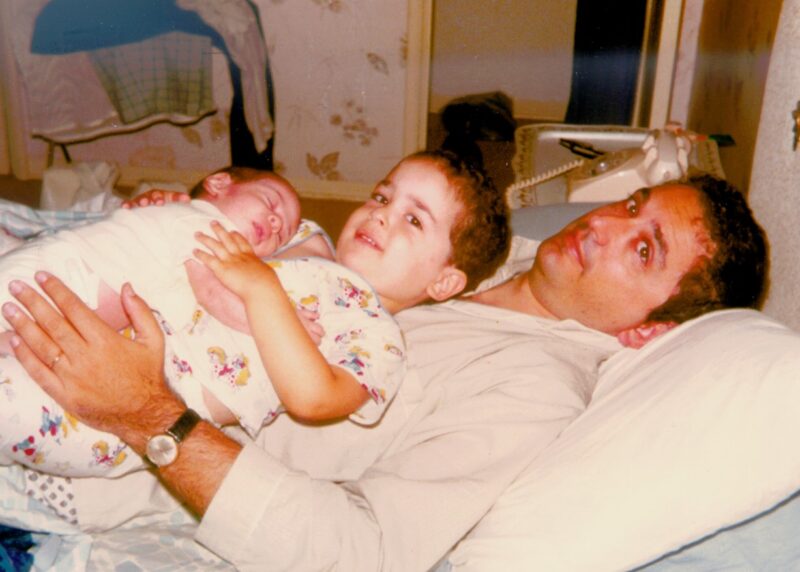

Below: my brother, me, my father (1971)

Further reading

On the birth of modern science: for a novelist’s dramatic and opinionated history, see Arthur Koestler’s The Sleepwalkers. For a physicist’s perspective see Steven Weinberg’s To Explain the World. For an exhaustive recent reassessment by a professional historian see David Wootton’s The Invention of Modern Science. For a shorter synthesis, the answer to “Why England?”, and many more references, see chapter nine of Loonshots (“Why the world speaks English”).

On the solar neutrino mystery

- My father at nobelprize dot org: Solving the solar neutrino puzzle; more technical history here.

Quote for the week

- “Prepare the child for the road, not the road for the child” -Folk wisdom, cited in Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff’s The Coddling of the American Mind

Read more Letters

Read the Five Laws of Loonshots

“A groundbreaking book that spans industries and time” –Newsweek

“If the Da Vinci Code and Freakonomics had a child together, it would be called Loonshots” –Senator Bob Kerrey