Vaccine news, the NBA, and Sending Kids to School

Vaccine news

Monoclonal antibody treatments (Regeneron, Lilly) and vaccines both continue to show encouraging results (good spreadsheet tracker here and visualization tool here). Much more data (phase 3) is expected in the fall. Although anything can happen in drug development, odds look good for FDA approval and limited roll out by end of year.

What’s most encouraging to many of us who have worked in drug discovery is not only the astonishing number of new drug candidates, developed so quickly, but also the diversity of mechanisms of action, meaning how the drugs and vaccines target the virus. The 200+ vaccine candidates (two dozen already in clinical trials) use a wide range of delivery mechanisms (how they get antigen into the body) as well as choice of antigen, meaning the piece of the virus presented to the immune system to teach it to attack.

Drug discovery is a shots on goal game, not a magic bullet game. For example, developing an anti-viral vaccine may be challenging, but it’s not nearly as difficult as an anti-cancer vaccine. For treating cancer, we need the immune system to attack the body’s own cells but *only* malignant cells, not healthy cells. In difficulty, that’s like asking an elephant to stand on its toes while playing a trumpet.

Cancer immunotherapy eventually succeeded (recognized with a Nobel prize in 2018) in large part because of the diversity of approaches that were tried. The earliest approaches failed. The mechanism of action that now works best — targeting an immune system checkpoint called PD1 — was not the one that early pioneers bet on, including those who won the Nobel prize. (For an excellent history see Charles Graeber’s book. It’s one long, amazing case study in the Three Deaths of the Loonshot.)

Bottom line: The immune system is a strongly interacting system, which makes it very difficult to predict what will and won’t work. Linear explanations don’t work well for nonlinear systems. Which means we need lots of experiments, with a diverse range of mechanisms. And that’s exactly what we have. (For more on this – I spoke with Molly Wood about vaccine research on Marketplace recently.)

Speaking of nonlinear systems …

Reports of rapidly fading antibody counts

Last month two small studies (papers here and here; a more recent small study here) suggested that levels of anti-covid antibodies in the blood, following infection, might decline rapidly. (Antibodies are the small soldiers that circulate in your blood and identify and destroy bad guys.)

Within minutes, media headlines declared that vaccines against covid might not work and even a prior infection might not spare someone from coming down with the disease a second time. The stories omitted many important details (the results were for patients with the weakest response to the virus, where one would in fact expect the lowest antibody response). But the most important caveat to keep in mind is that all three studies measured only the levels of a certain type of antibody. That antibody type is just one component of a immune system with many strongly interacting parts. Once again: a linear explanation in a strongly nonlinear system.

As this study shows, SARS-CoV-2 can induce a virus-specific memory T-cell response, which is critical. Why? Just because your computer’s CPU isn’t burning up with anti-virus software on full throttle 24 hours / day doesn’t mean that your computer is vulnerable. What’s important is that the anti-virus software running in the background has the right code to detect malware. The memory T-cells are that code. Circulating memory cells is your body’s anti-viral software running in the background.

More here and here on why concerns may have been exaggerated.

Side note: the mistake of applying linear explanations to nonlinear systems is at the root of many unexplained mysteries in economics and finance: bubbles, crashes, excess volatility, anomalous returns. I briefly described this in chapter 6 of Loonshots. More details along with a new way to think about those old problems — a new theory of phase transitions in financial markets — will most likely be my next book.

One final note (for this letter)

Although delivering a vaccine at scale under normal circumstances might take a year or longer following Phase 3 data, these are of course not normal times. Nearly every vaccine developer has invested at massive levels in building manufacturing capacity far ahead of Phase 3 data.

AstraZeneca, for example, has partnered Serum Institute, which expects to begin delivering hundreds of millions of doses in the first quarter of 2021. There’s much more to say about this … perhaps for another letter.

From hoop shots to loonshots

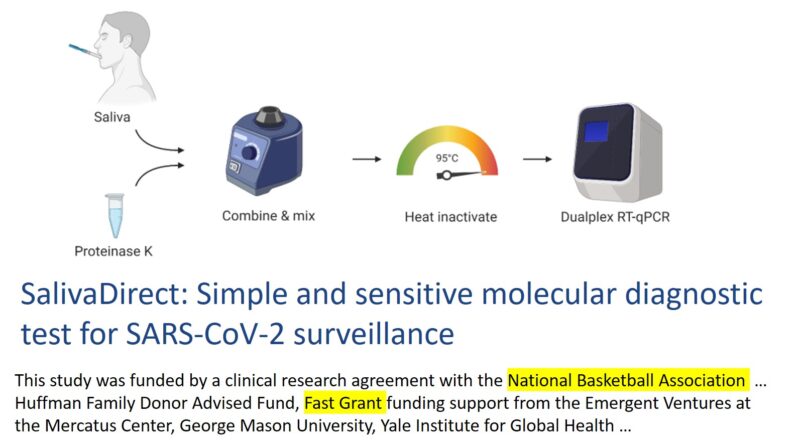

We need much faster turnaround time on test results. This rapid saliva test, which was submitted for FDA review last month, could help. It’s accurate, fast, and cheap (<$5 per test).

And I was delighted to see the research was cosponsored by the National Basketball Association (!) and Tyler Cowen’s Fast Grants program at George Mason University, designed to fund wild new ideas for covid with minimum red tape. Fast Grants is backed by Elon Musk, Chris Sacca, the Collision brothers, and many more.

The Fast Grant program, in turn, was inspired by the story of Vannevar Bush’s loonshot nursery in World War II. And that, of course, is the subject of chapter 1 of Loonshots.

Sending our kids to school, and the risk in the tail

While median rates of severe complications or death from covid are low for those under 50 with no preexisting conditions, what’s important to keep in mind is the risk in the tail end of the curve. We still don’t know how long the effects of the disease can persist. Examples include signals (still early) that damage to the heart or lungs might be long lasting, as well as this study, a review of published data on acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), which found that 20% of patients who experienced ARDS suffered cognitive impairment five years later. Covid of course can cause ARDS.

The #1 rule to keep in mind about statistics is to look at the shape of the curve, for both probabilities and severity, not just the median. (For a great read on how media so often gets stats wrong see Jordan Ellenberg’s How Not to Be Wrong.)

That’s exactly what Sanjay Gupta does in this essay, describing why he has decided not to send his kids to school, in person, in the fall.

We’re still thinking this through, in my home, but are almost there.

Quote for the week

Hofstadter’s Law: “It always takes longer than you expect, even when you take into account Hofstadter’s Law.”

I’m finding that comforting right now.

Read more Letters

Read the Five Laws of Loonshots

“A groundbreaking book that spans industries and time” –Newsweek

“If the Da Vinci Code and Freakonomics had a child together, it would be called Loonshots” –Senator Bob Kerrey